In the middle of his whopping press tour for A Complete Unknown, Timothée Chalamet posted a livestream to his 19.6 million Instagram followers which was delightfully bizarre.

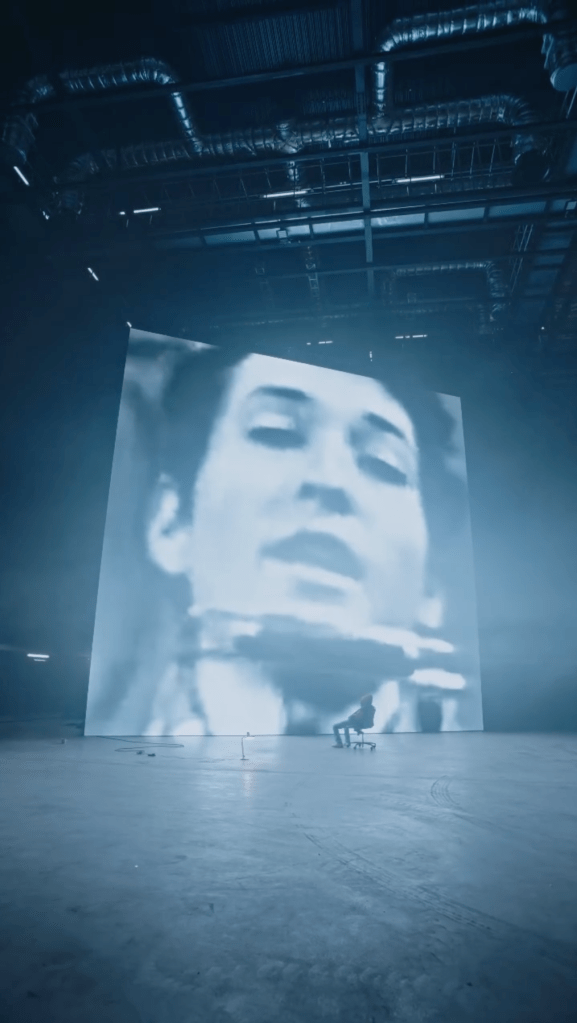

Set in what looks like an industrial warehouse, the livestream opens with the sound of Bob Dylan’s guitar. The (phone) camera moves slowly through the space, revealing a colossal screen at the back of the room projecting a pixelated, lagging video of Bob Dylan performing his 1991 track Blind Willie McTell. In front of it, Timothée Chalamet swings gently on an office chair. The song plays on, consuming the star of the Dylan biopic beneath its might. This shot feels like he’s the last one left at the cinema, maybe in this case watching his own film, or the last Bob Dylan fan lingering after a show – not quite ready to leave and return to the real world.

The livestream was directed by Glaswegian photographer Aidan Zamiri. A 29-year old who’s been behind some of this year’s most defining cultural visuals. Think Charli XCX’s 365 and Drive music videos – cultural moments in themselves that capture the hyper-online aesthetic of our current creative moment with humour, irony, and fun. They feel like the internet’s own hall of mirrors, endlessly looping self-referential takes on celebrity culture. Through his work, Zamiri ignites these buried feelings of digital nostalgia, I guess meme-like in themselves. In his own words from his Dazed 100 interview, he says: “Like a lot of people my age, I have so much access to so much content all the time that I have this eclectic muddle of stuff in my brain that I feel sentimental about. (This) creates this weird feeling of nostalgia for things that I haven’t necessarily experienced myself or don’t even fully understand.” His work does exactly that – a nostalgia for the internet itself, in all its glitching satirical glory.

There is a sense of this digital nostalgia universally, with the rise of ‘shit-posting’ and hyper-saturated filters bringing us back to 2012 retrica. Maybe it’s a reaction to today’s hyper-commercialised influencer culture, where we’re constantly sold ‘authentic’ glimpses of celebrity lives and can never be sure when we’re being sold things. It’s almost impossible now to find a corner of the internet that isn’t monetising your engagement, hoarding your data, or owned by one of the richest men on the planet.

This centralising of the internet as an agent itself is a key discussion in the 2023 publication POST POST POST; a collection of essays that set out to define our new era beyond post-post modernism towards an endless self-referentiality and beyondness that is evidenced in our creative avant-garde today. It forefronts memes as a cultural driver, not just a product of culture. Like Timothée Chalamet’s livestream, this POST POST POST view looks to Instagram and other social media platforms as a medium for its most famous inhabitants to create cultural moments as opposed to just documenting them.

In some ways, I regret not being online as much as I was when I was younger, though not entirely, since maybe stepping back is what led me to these reflections on the internet in the first place. The resurgence of ironic celebrity culture and endless cycles of online self-referencing isn’t exactly new, but its current delivery feels creatively exciting. Maybe I’m still stuck in that loop after reading Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger, hyper-aware of the ways we duplicate ourselves online. What’s really struck me during my year off from uni, where I was writing thousands and THOUSANDS of words on literally anything I wanted, is how much my sense of what I want to say has changed. Maybe it’s from working and spending more time outside the theoretical discourse bubble that’s so easy to fall into at Goldsmiths. A lot of the ideas that once gripped me now feel less urgent, less electric, without the constant deadlines to churn out 4,000 words on a chosen academic target within a three-week break. My visual cultures degree felt like a lifeboat away from the sinking ship of the online world, but I never wanted to write about the internet. The most ‘techy’ thing I ever wrote was about was Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto. But something shifted in the lead-up to this last American election. Paired with the surge of digital nostalgia online, it suddenly feels like everything I want to say is already filtered through these lenses – perhaps because our visual culture now almost always reaches us first through our screens.

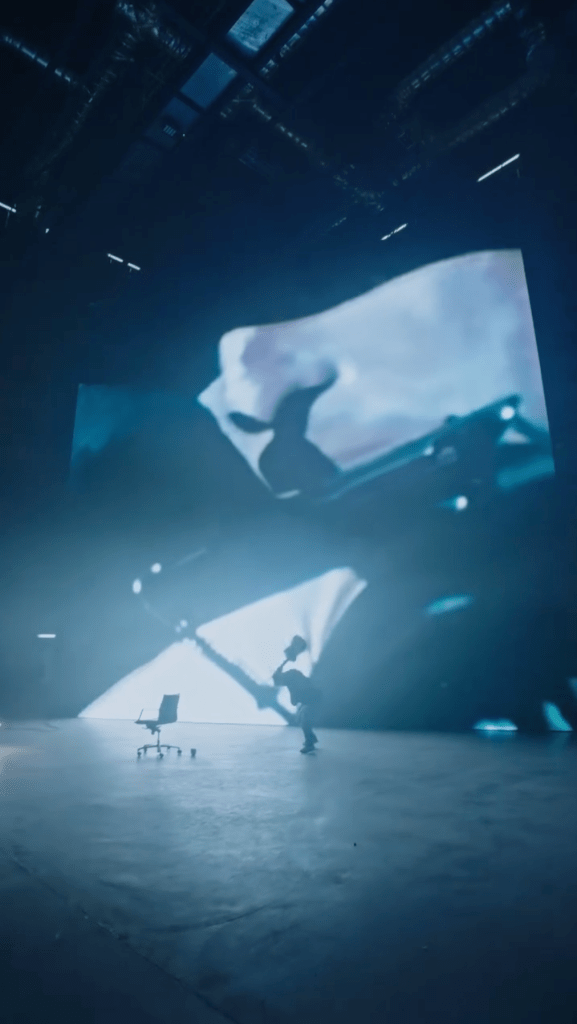

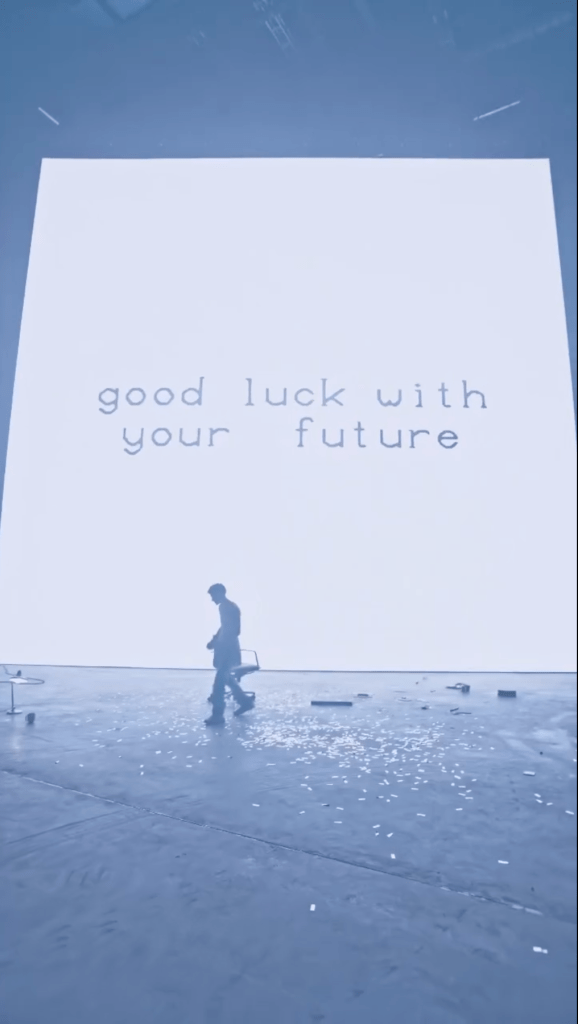

So there I was on Christmas Day, watching Timothée Chalamet on my phone as he sat in front of a massive screen for the entirety of Dylan’s grainy Blind Willie McTell performance. Eventually, towards the end of the song, he smashes a guitar violently on the floor. The screen cuts to black, and the unmistakable opening notes of the Black Eyed Peas’ I Gotta Feeling take over. (My first concert ever, thank you Mum.) Timothée’s out of the chair now, and the screen lights up with words of praise while anonymous bodies sneak into the shot to embrace him: “You did it,” “good luck with your future.” We can’t quite tell if this celebration is genuine or satire. It feels like these comments were pulled directly from his Instagram, with one even spelling his name wrong. He keeps moving, waltzing across the concrete expanse with a confetti gun, hip-thrusting to I Gotta Feeling until he exits stage left, with the camera following him around the industrial park in silence. The whole thing lasts 14 minutes.

The internet had no idea what it was watching: a comedy bit, performance art, or a genuine celebration of a monumental moment in his career, playing Bob Dylan in his biopic, earning him an Oscar nomination and huge box-office success. The whole thing is shot on what looks like a phone, no stabiliser, no face-tracking tech, just someone holding a (phone) camera and following this “Lil Timmy Tim” (another facet of his rich digital footprint) as he floats through the sprawling set around him.

It’s Hollywood’s most relevant heartthrob rejecting the polished tools of the untouchable celebrity, paparazzi, Facetune, carefully curated public appearances, and embracing the tools of the masses: social media and chaos. His and Zamiri’s use of a livestream format shortens the distance between creator and consumer. The whole thing feels like a perfect sign-posting for our moment, the internet as the art itself, all of us dancing within it performing authenticity or authentically performing.

What was this livestream? Was it performance art, was it self-indulgent madness (the Daily Mail’s take), or a complete unraveling after five years of preparing for this role – a hyper-meta POST POST POST live-streamed meltdown? Five years spent learning to look, sound, and become Bob Dylan would do strange things to you. Maybe this chaotic performance was his way of closing his own surreal doppelganger chapter, going out with a euphoric Black Eyed Peas bang. Or maybe its just Aidan Zamiri and Chalamet rejecting the sterile, hyper-curated digital world we’ve built and having FUN with the platforms they’ve inherited. Across the board, Zamiri’s work, above all else is fun. Maybe that’s the antidote to the double-edged sword of cancel culture that now dominates online spaces. Perhaps irony is the escape from the false sincerity celebrities adopt in an attempt to dodge becoming the next victim of public takedown. I’m not entirely sure what this was, but the whole thing brought me enourmous joy. There’s something hugely exciting about the strange nostalgia Zamiri and Chalamet tap into. It feels like the internet fighting back against itself. It made me hopeful for this new era of visual culture – undefinable and messy. As with all great avant-garde movements driven by new media and technology, the internet in its evolving form means its original, glitchy and imperfect form is once again a subversive medium in its own right. It’s the internet eating itself.

I want more of Aiden Zamiri,

More chaotic Timothée Chalamet press tours,

And definitely more fun.

Thank you Timothée Chalamet and Aiden Zamiri. Check them both out on Instagram.

Aiden Zamiri Dazed 100 –https://www.dazeddigital.com/projects/article/48851/1/aidan-zamiri-photographer-filmmaker-biography-dazed-100-2020-profile

all images © Timothee Chalamet / Instagram